What do judges do? Justice Clarence Thomas has explained it this way: “We interpret and apply written law to the facts of particular cases.” Sounds simple enough. But while everyone can read what our laws say, the question is how much power judges should have over what they mean.

America’s Founders were well aware of this. They wanted to minimize what Alexander Hamilton called “arbitrary discretion” by judges, designing a system in which judges must interpret the Constitution and statutes by determining what their authors meant by what they wrote. Today, this approach is called originalism.

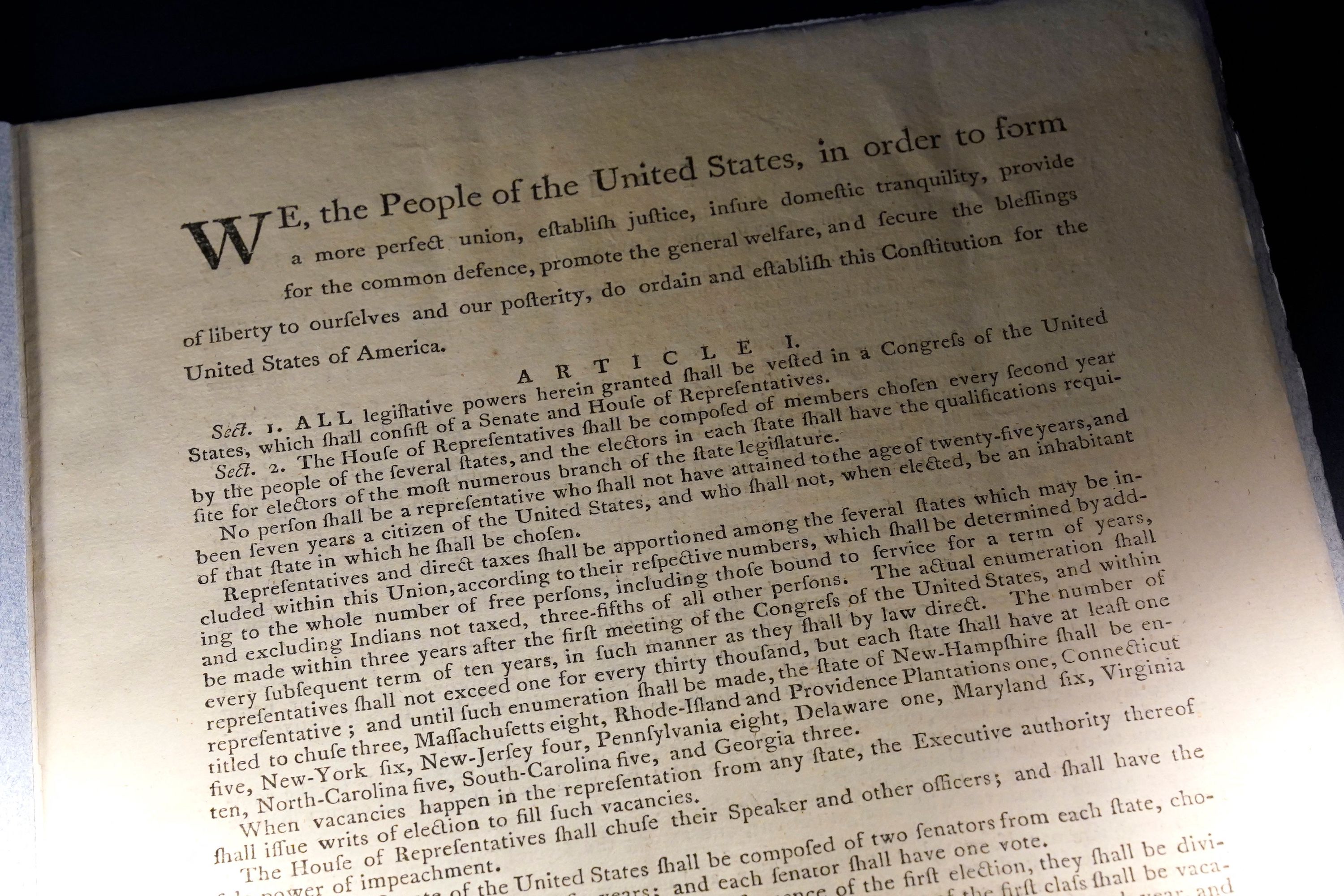

Three features of the Founders’ design support this conclusion. First, America is a republic where, Hamilton famously explained, “the people govern.” The Constitution is the primary way that the people set rules for government, which includes the judiciary. Back in 1795, the Supreme Court asserted that the Constitution “is fixed and certain; it contains the permanent will of the people, and…can be revoked or altered only by the authority that made it.” That authority is the American people.

“Altering” the Constitution obviously includes changing what it says, but that would be a hollow exercise unless the American people also determined what its words mean. In a 1937 opinion, Justice George Sutherland wrote that judges changing the meaning of the Constitution really amounts to “amendment under the guise of interpretation.” Judges do not have authority to amend the Constitution.

Second, as Marbury v. Madison explains, the Founders wrote the Constitution down so that its rules for government “may not be mistaken or forgotten”—rules intended, the Court said, to govern courts as well as legislatures. Needless to say, the Constitution cannot control judges if judges can control what the Constitution means.

Third, in schools that still teach civics, students learn that the government has three branches that do different things. The legislative branch makes the law, the executive branch enforces it, and the judicial branch interprets it. Interpreting and making the Constitution or statutes, therefore, must be different.

Another reason originalism is the appropriate method for interpreting the Constitution and statutes is that the Founders, who designed our system of government, said so.

In his 1796 farewell address, President George Washington wrote that changes to the Constitution should take place “by an amendment in the way which the Constitution designates” rather than through “usurpation.” James Madison insisted that the guide for “expounding” the Constitution should be “the sense in which the Constitution was accepted and ratified by the nation.” And Thomas Jefferson argued that “on every question of construction,” we must “carry ourselves back to the time when the Constitution was adopted, recollect the spirit manifested in the debates, and instead of trying what meaning may be squeezed out of the text, or invented against it, conform to the probable one in which it was passed.” This instruction flows directly from the system of government these Founders designed.

In his book, A Republic, If You Can Keep It, Justice Neil Gorsuch writes that “originalism is a theory focused on process, not on substance.” In other words, judges should interpret the Constitution and statutes by their original public meaning and apply it impartially no matter which party wins or what political interests might be furthered. Gorsuch points to several decisions in which, as an appellate court judge, his application of originalist principles led to liberal results. The point is, if the political ends justify the judicial means, if judges can simply look for whatever interpretation will produce the results they want, judges control the law.

When judges abandon what the Constitution and statutes actually mean—that is, what “the authority that made [them]” meant—then judges, and not the law, determine the outcome of cases. The Constitution becomes, in Thomas Jefferson’s words, “a mere thing of wax in the hands of the judiciary, which they may twist and shape into any form they please.” If the judiciary controls the Constitution, the people do not, and it ends up expressing the judges’ will rather than theirs.

In chapter six of Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass, Humpty Dumpty says to Alice: “When I use a word…it means just what I choose it to mean—neither more nor less.” Alice asks “whether you can make words mean so many different things.” Humpty replies that the question is “which is to be master—that’s all.”

The people can be their own masters, governing themselves, only if they, and not judges, control what the Constitution and statutes both say and mean.

Thomas Jipping is a Senior Legal Fellow in the Meese Center for Legal and Judicial Studies at The Heritage Foundation.

The views expressed in this article are the writer’s own.