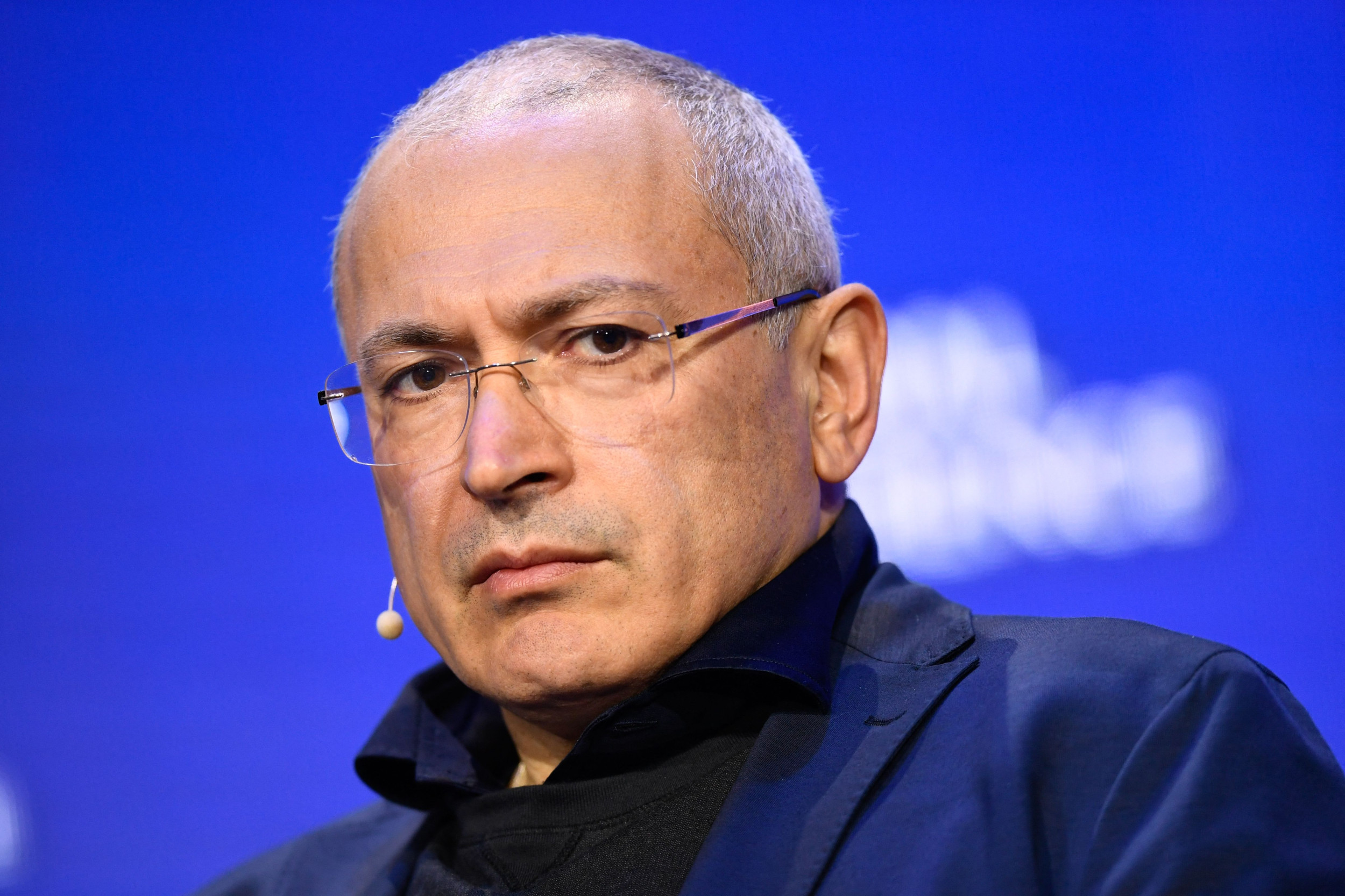

Mikhail Khodorkovsky raised both eyebrows and hackles from other Russian opposition figures when he welcomed Yevgeny Prigozhin‘s move against Vladimir Putin‘s authority—after all, the late Wagner founder was no textbook revolutionary.

But Khodorkovsky, an exiled tycoon who himself has ran foul of the Russian president, believes that the person who makes the first move to wrench Russia from autocracy may come from unexpected quarters.

“It was quite adventurous what Prigozhin did but it was not a revolution,” Khodorkovsky told Newsweek regarding the Wagner chief’s seizure of military facilities in Rostov-on Don and his march on Moscow. Revolution in Russia and its difficult aftermath is what his book released later this month, How To Slay a Dragon, is all about.

Khodorkovsky headed the energy company Yukos before being jailed on what were deemed politically motivated charges after speaking out against corruption. Following a decade in prison, he was pardoned by Putin in 2013, and has continued to be a leading critic of his regime.

Speaking to Newsweek from the London headquarters of his activities, which includes the Open Russia Foundation he founded, Khodorkovsky said it was notable Prigozhin’s move on June 24 did not aim to shift the occupant of the Kremlin.

“He had an absolutely gangster idea. He wanted to exert pressure on Putin,” he said, “there was no plan to change the regime.”

As the biggest challenge to Putin in his 23-year presidency unfolded, Khodorkovsky posted on X (formerly Twitter) how Prigozhin should be supported in his march on Moscow because it dealt a blow to Putin’s legitimacy.

“People were quite offended by the idea we needed to help Prigozhin reach Moscow,” said Khodorkovsky. Anyway, he did not believe Prigozhin was the man to take over Russia—far from it—but he saw his mutiny as possibly kick starting a process which could split Putin’s power and usher in other opposition forces to end Putin’s rule.

But it might mean those in the West may have rethink the idea of the “heroic opposition” overturning autocracy in Russia, “because if power is consolidated on the other side, no opposition can remove it.”

The Belarus lesson

If the late Wagner chief’s failed coup showed how change might occur in Russia, the Belarusian opposition fight against the Russian leader’s ally, Alexander Lukashenko in 2020 provided a starker lesson.

Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya is widely thought to have defeated the only post-Soviet leader Belarus had known and her opposition movement was co-ordinated, mobilized and had the moral support of the West. But for Khodorkovsky, one key thing was missing,

He said hopes of change in Belarus finished the moment the opposition gave up the liberation of political prisoners at Minsk’s Okrestina Detention Center, partly because it deprived the push for democracy of the momentum and leaders to complete the ouster.

“If there is no threat to forcefully replace the regime then no dictatorship would leave of their own accord,” he said. “If the dictator thinks that it can cope, it will try to cope and the result would be a lot of bloodshed,” he said.

Violence may not be essential, but, “I don’t know an examples of any dictatorial regime, without the perception of violence, who would of their own accord say, ‘we will leave.'”

He accepts understanding the limits of peaceful protest to enact change in Russia may not have the backing of the international community and any push to change Russia would have to be decisive.

Khodorkovsky’s book cites Karl Marx’s view that you should never “play” at an uprising. Once it has started, the opportunity must be seized and carried through to the end.

Like during Prigozhin’s mutiny, he said enforcement agencies would need to take a step back and the most active part of society will have to try to break the resistance of the units backing the government who are willing to oppose the people.

The government must be pushed to a point where “they do not have enough force to withstand those civilians against them,” he said. “The moment the government understands the other side also has resources, then negotiations can take place.”

“If tomorrow some person ends up in Kremlin and he has control of the communication systems, and if that person has at least a minimum public popularity, then the powers that be in Russia would be changed.”

After Putin?

A post-Putin future for Russia would require swift action to consolidate a new Russia that Khodorkovsky believes would be in immediate danger of reverting to type. He dismisses any notion, proposed by the West or elsewhere that if “the bad guy leaves and the good guy steps in, everything will be fine—everything will not be fine.

“In two or three years, the good guy will turn into a bad guy and America will again become the enemy and it will go back to what it was,” he said, “the presidential figure in Russia is a very dangerous thing.”

Knocking flat Russia’s power vertical to a horizontal one will be a radical shift. “There is no other public experience,” he said, “it’s like when you sit down to the table and you’ve never seen a knife and a fork, you’ve only seen up a spoon. so you grab the spoon, even you have a piece of meat in front of you.”

Khodorkovsky’s book describes his vision of a unified Russia in which power is devolved into the regions by way of a parliamentary republic of which he considers the U.S. to be a de facto version, with the head of state having relatively little power over state matters.

“Federalization should happen straight away,” he said, with local rather than federal authorities presiding over the distribution of resources.

But two years would be the limit of trust that the Russian people would give to a reform program in uncertain circumstances. A Constituent Assembly, a new constitution and free elections needed to create democratic institutions would need to happen quickly.

Khodorkovsky also sees that many involved with the current government would be essential to rebuilding a new Russia, a situation unlike previous changes in power, or lustration, which eliminate those tied to the previous regime.

This is out of practicality because only around two million Russians in a population of 140 million have the professional skills to manage a state. Most of the judiciary would have to stay too.

“We could leave the federal authorities with a very limited number of authorities or powers,” he said, “and it’s quite feasible to balance the powers in the federal provinces of subjects with local self-governance.”

His book’s title is a nod to the Soviet-era film To Kill a Dragon, in which a character realizes to get rid of someone else’s dragon you have to create one of your own, a metaphor of how Khodorkovsky believes Russia’s cycle of autocracy can be broken.

He believes it is difficult to forecast when Putin will leave power but it will happen. “Most likely he will only leave power when he dies,” he said, adding “it is important to be prepared for the split in his circle” and to be able “to exploit the situation when it arises.”